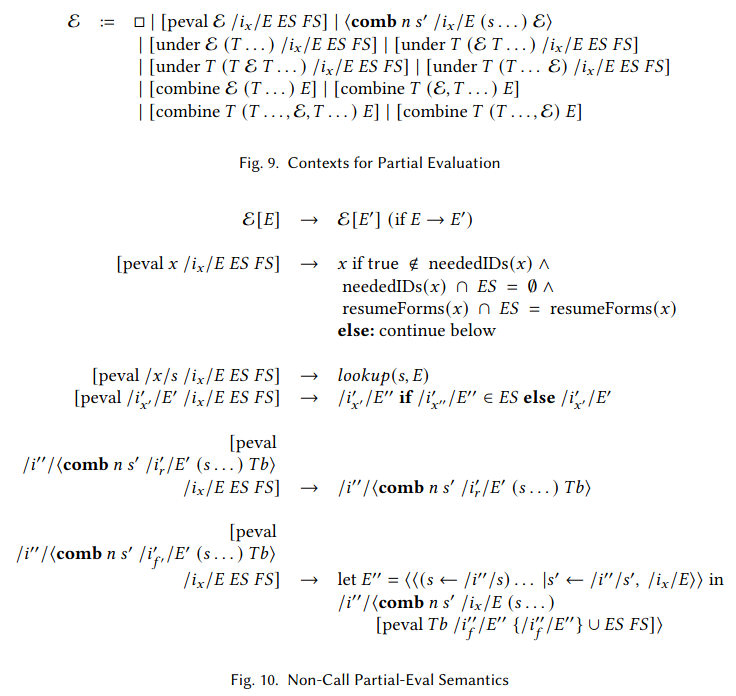

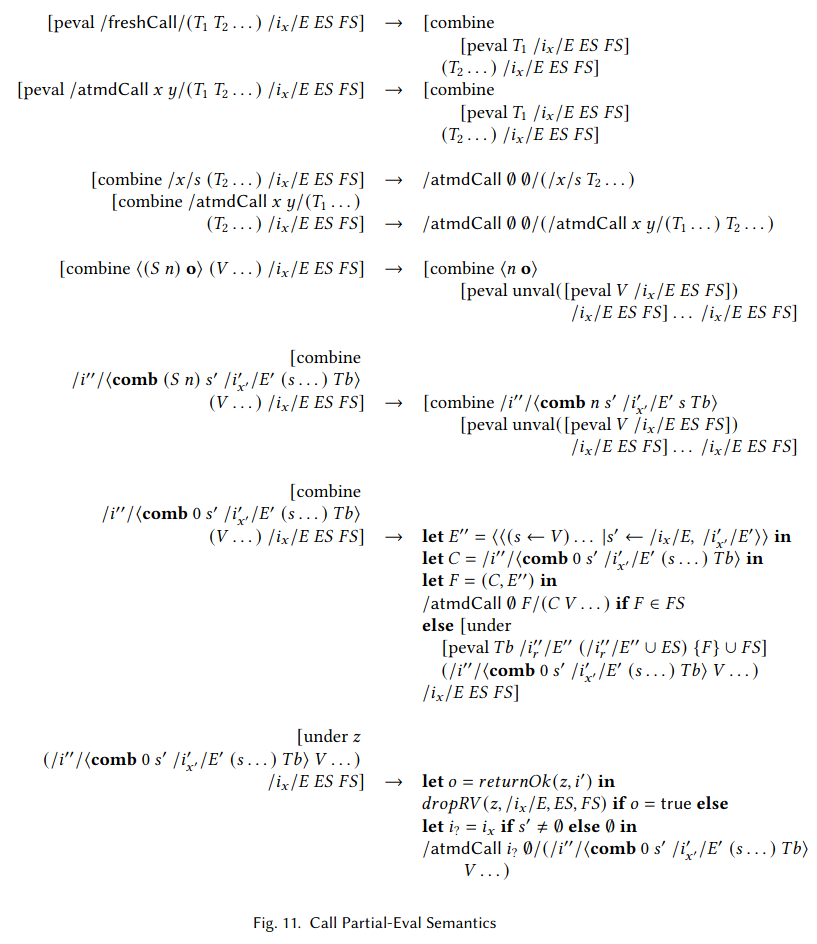

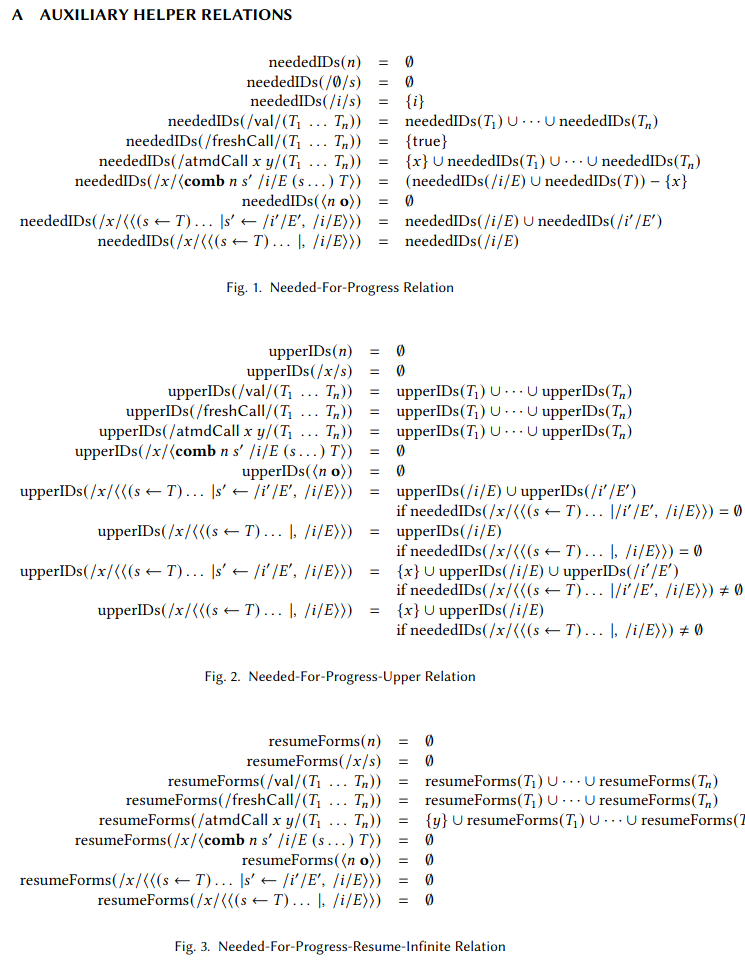

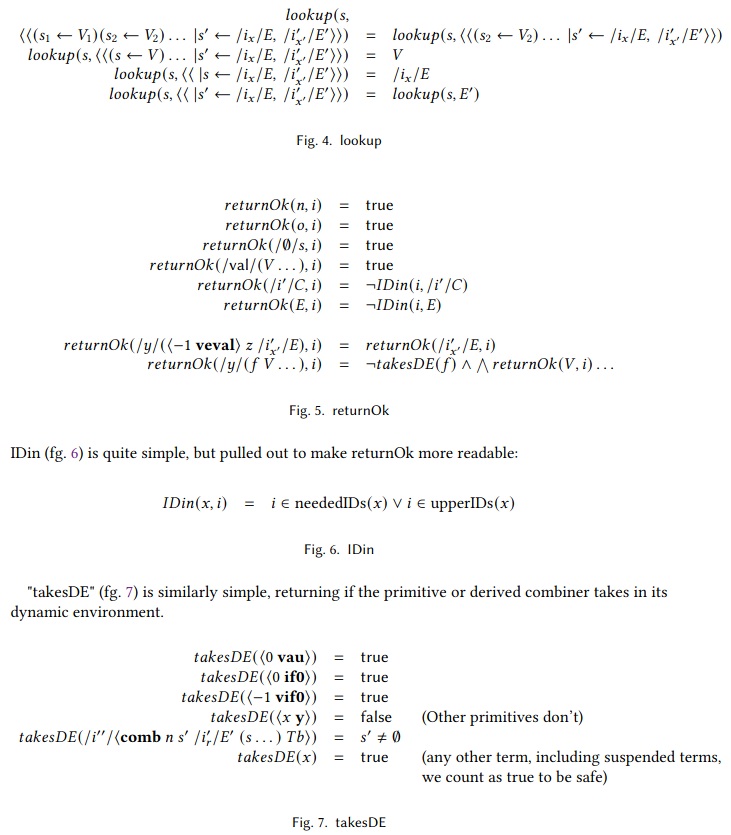

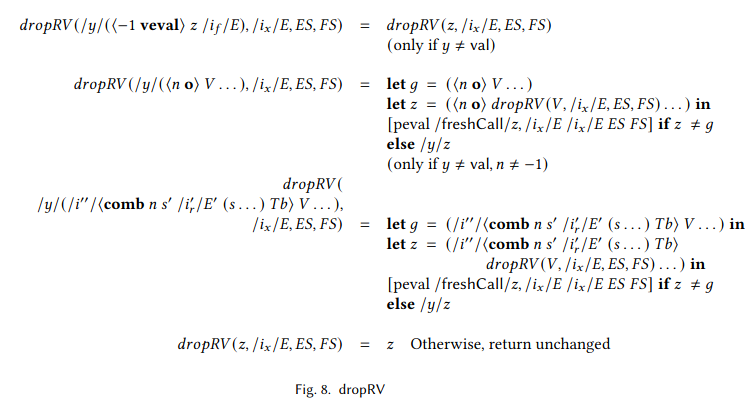

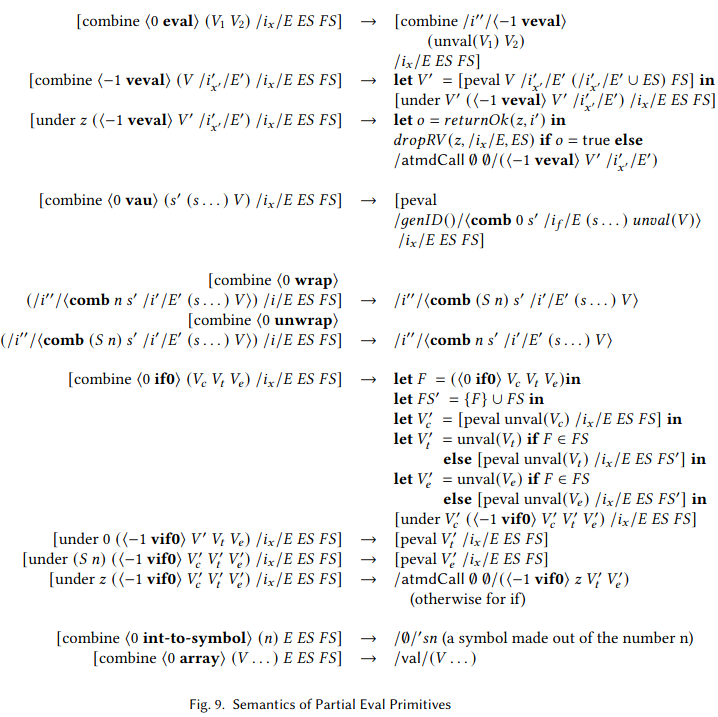

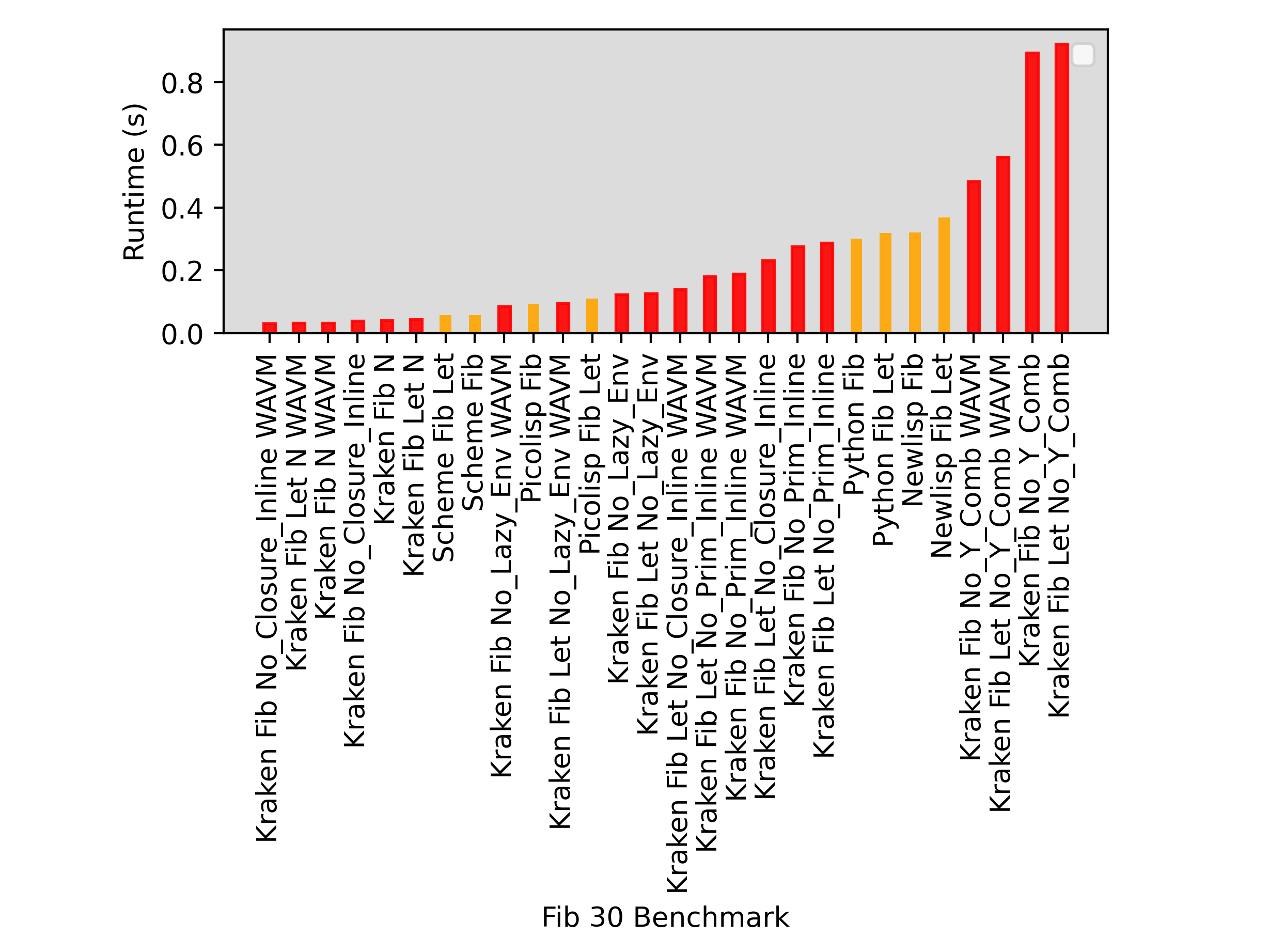

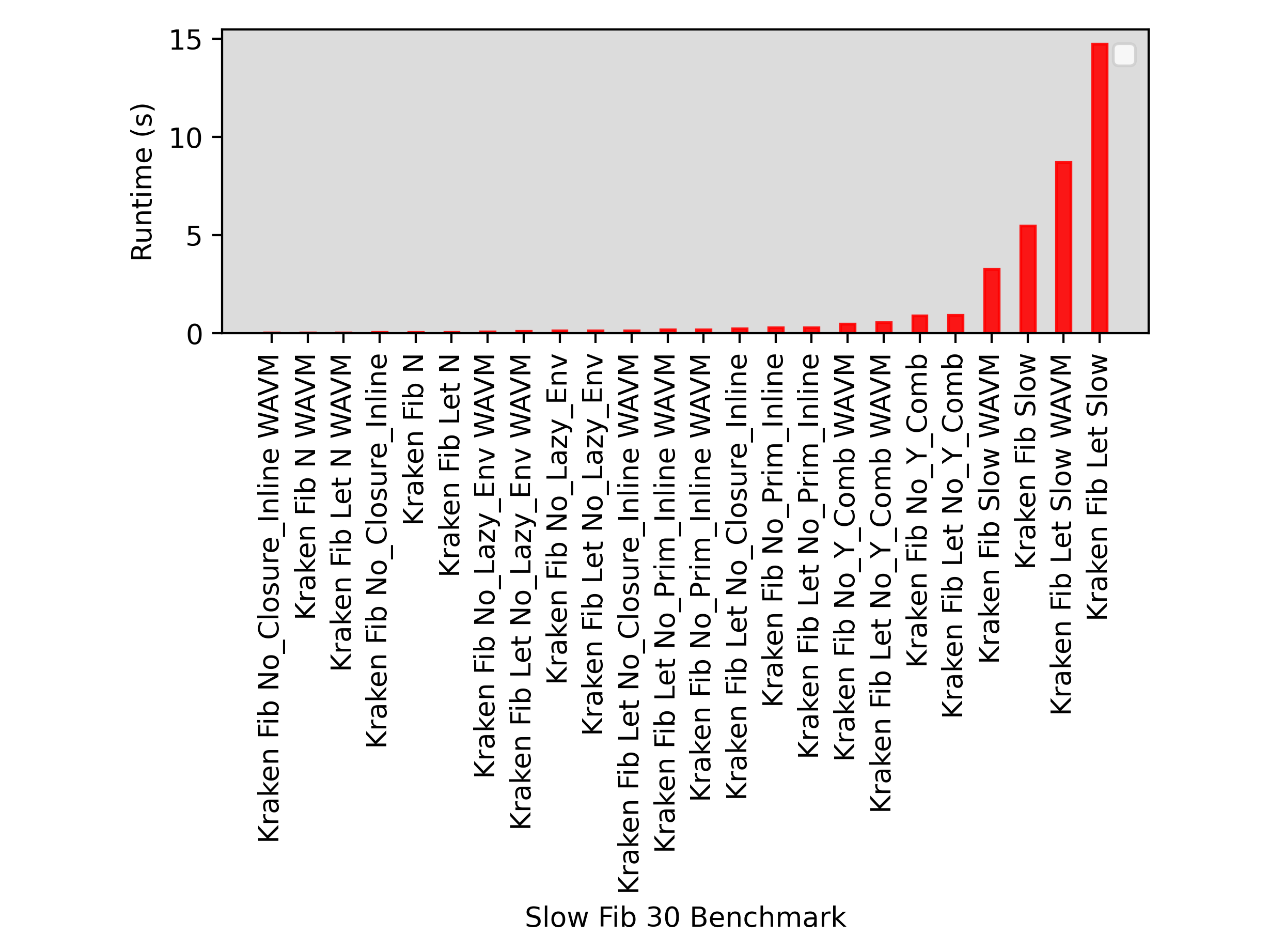

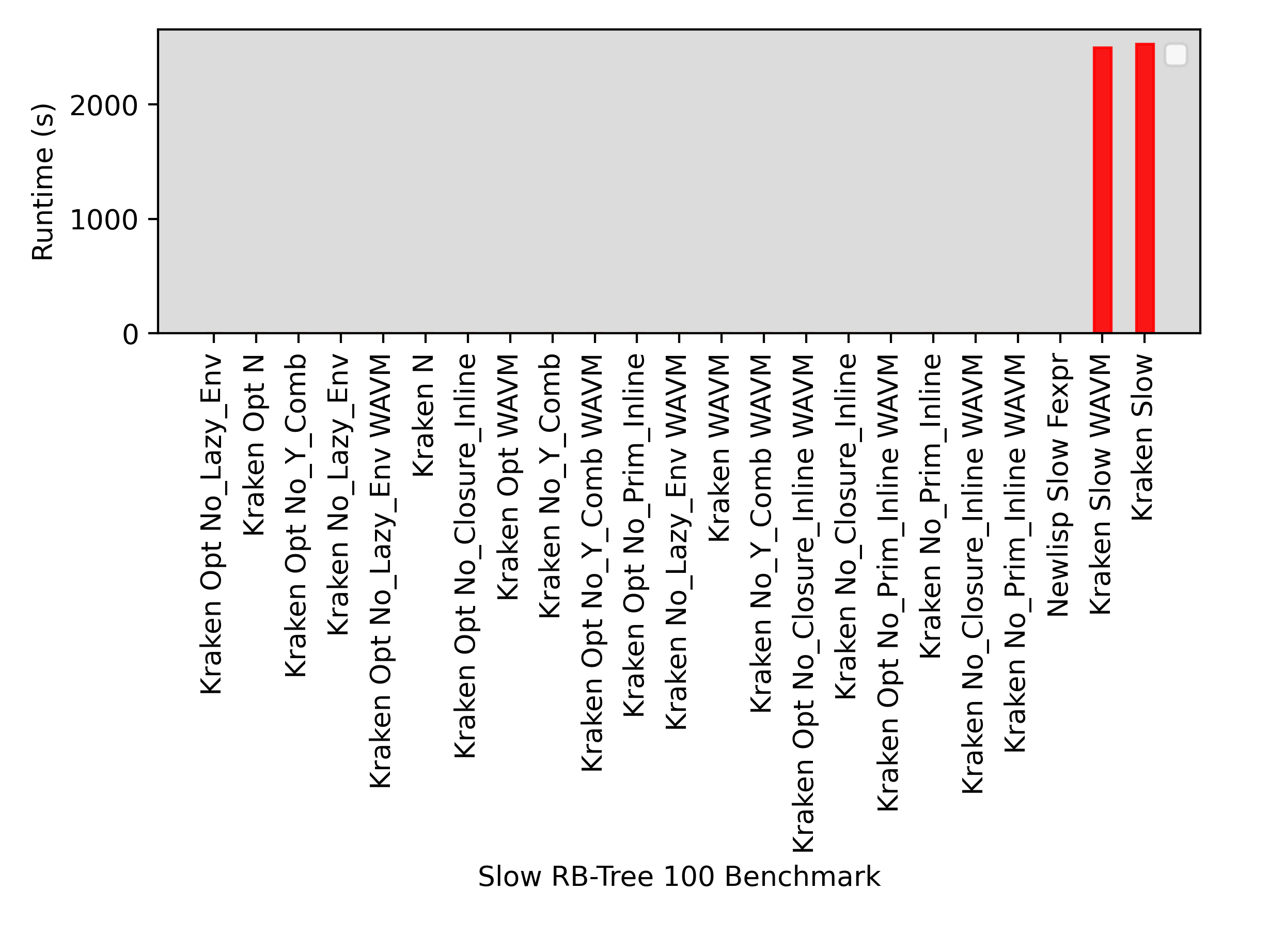

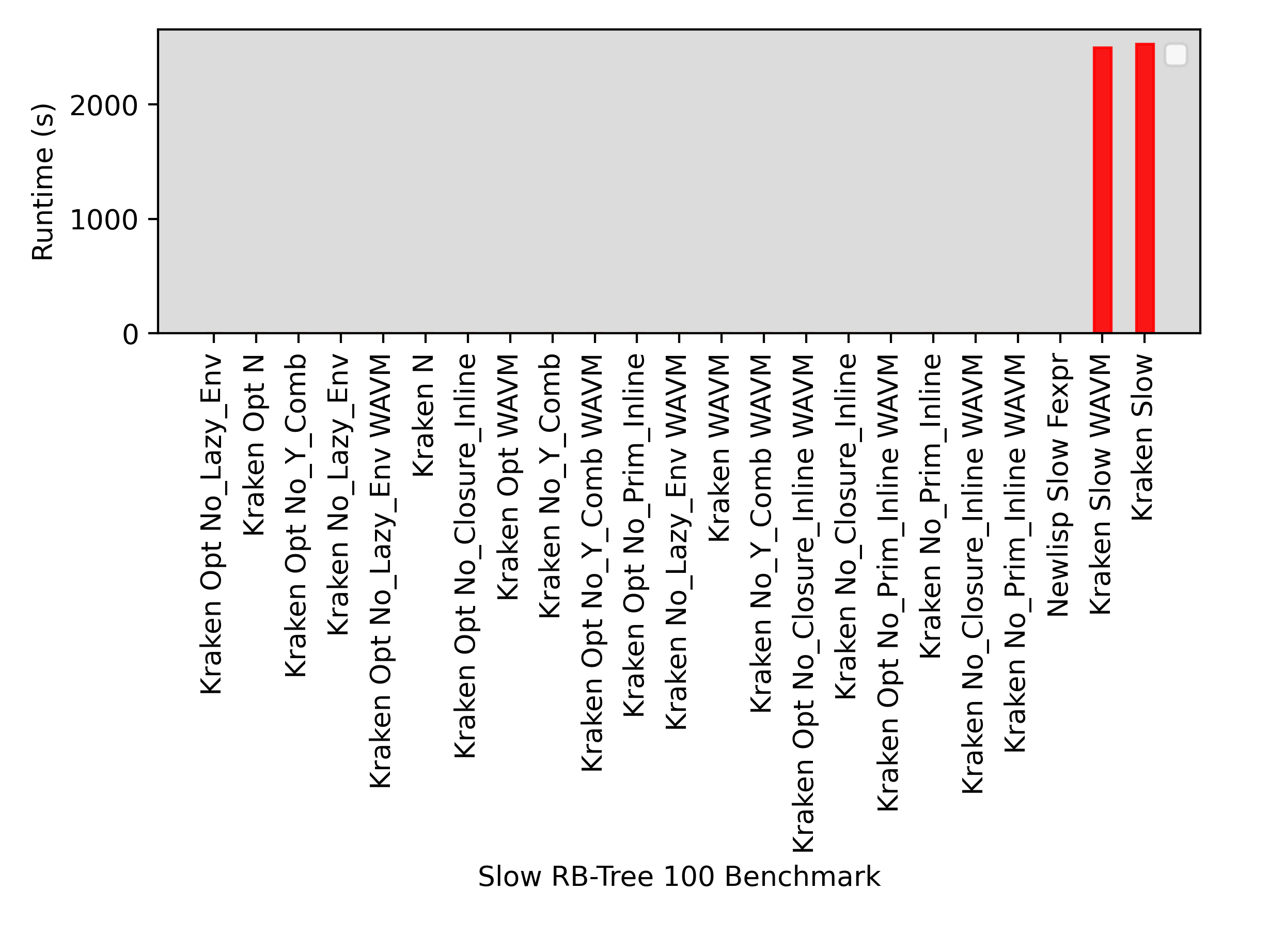

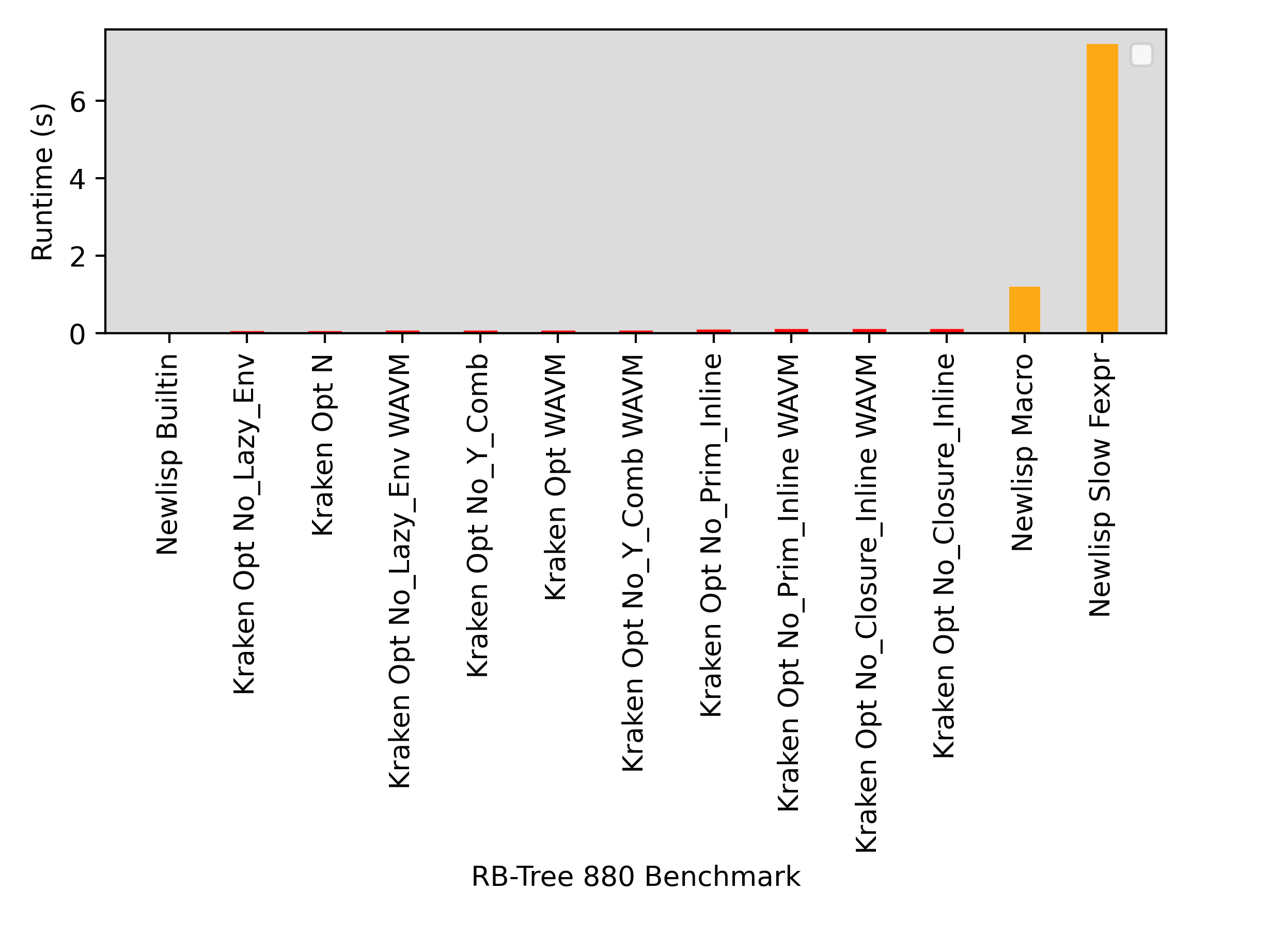

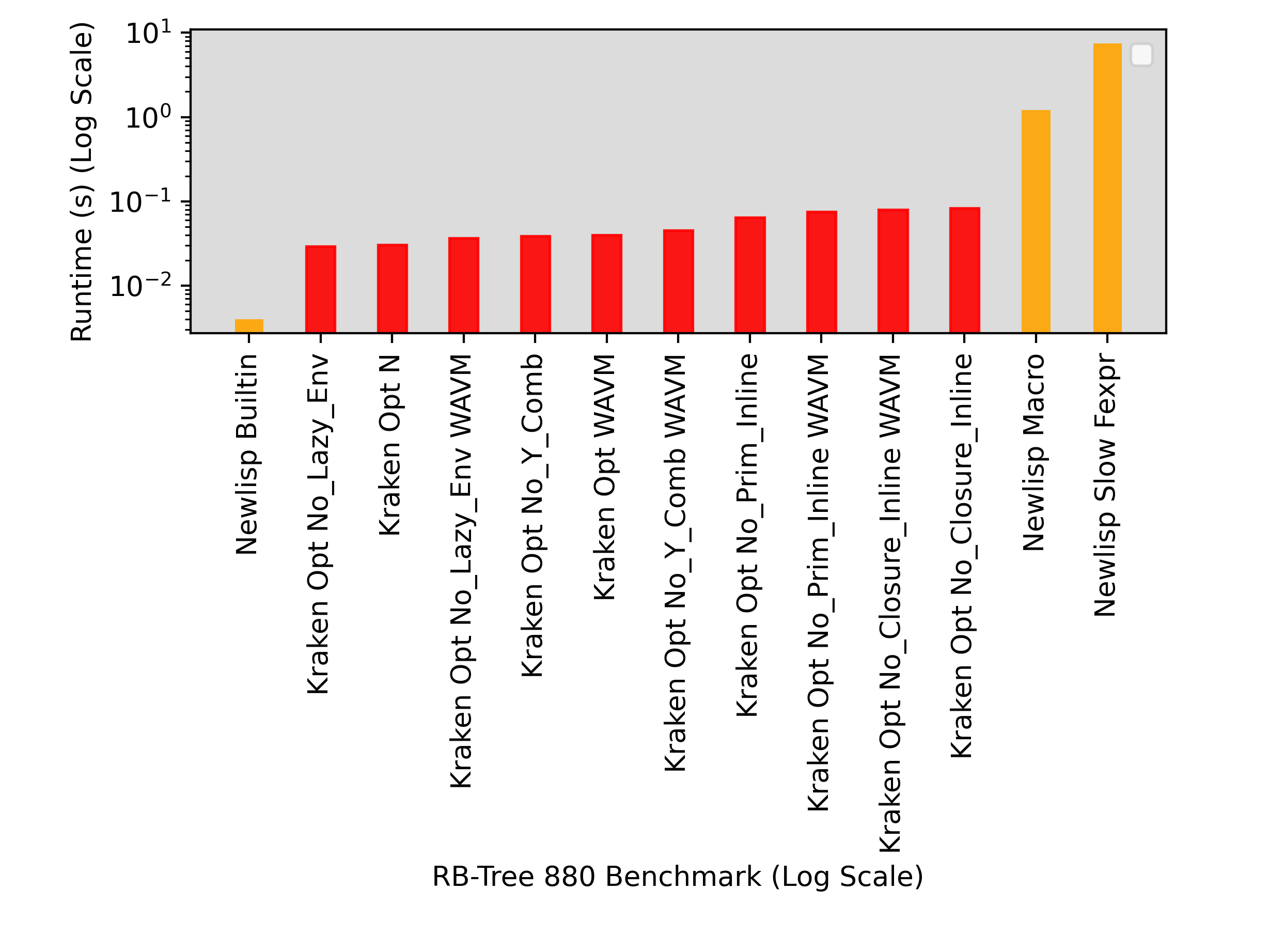

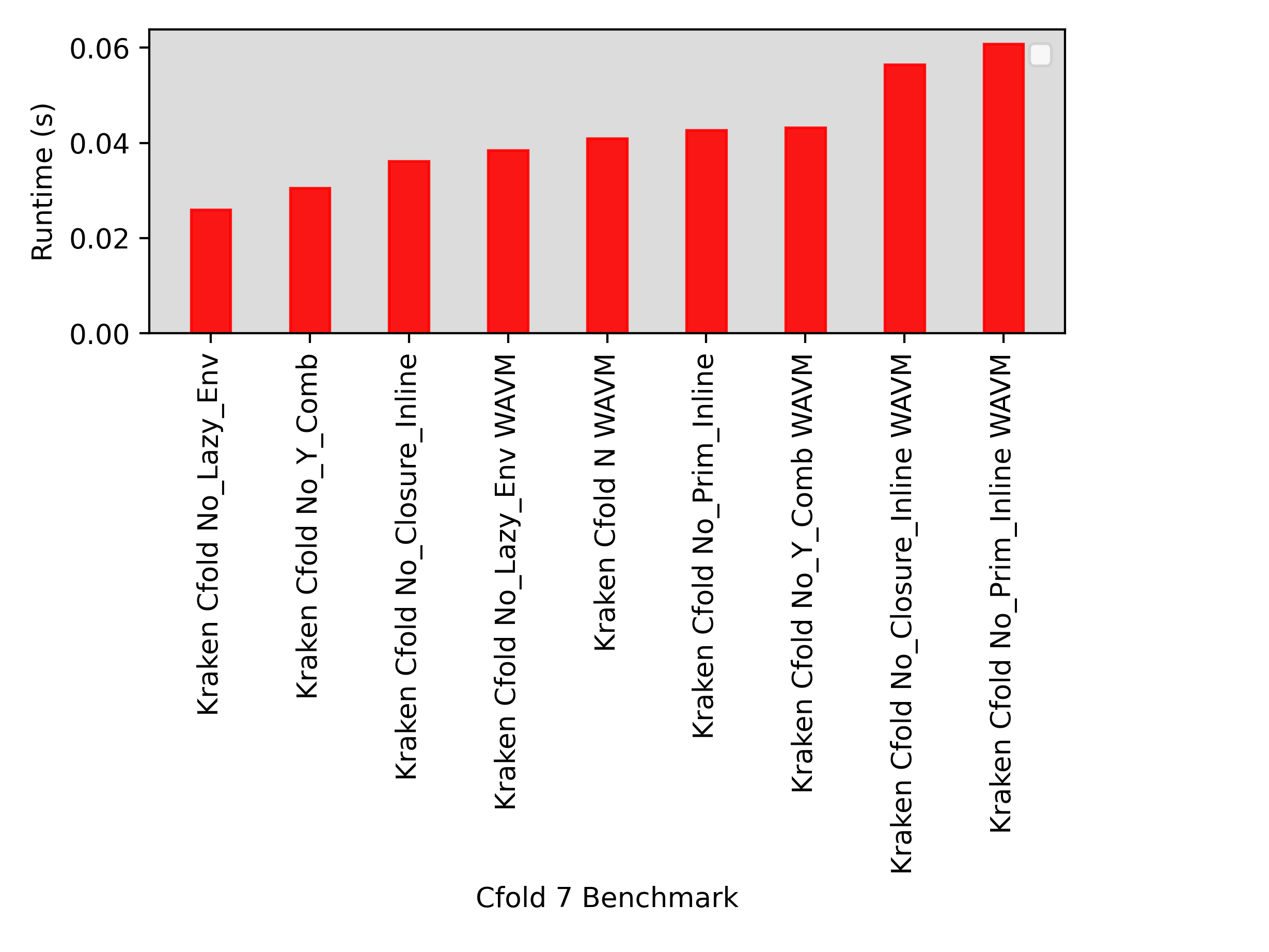

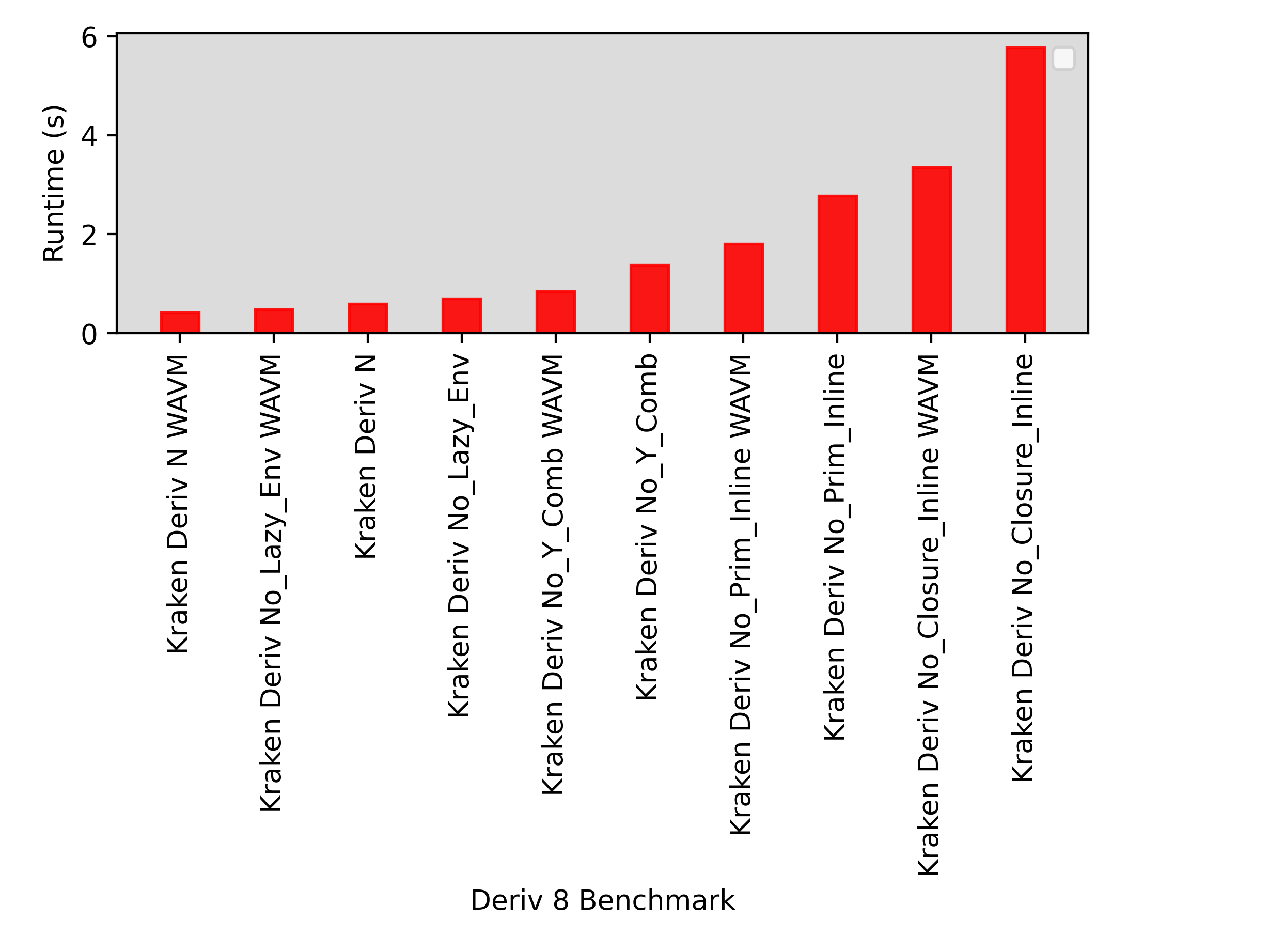

class: center, middle, title # Kraken _Fexprs are a better foundation for functional Lisps_ --- # Agenda 1. Fexprs Intro / Lisp Background 2. Macro and Fexpr comparison 3. Fexpr problems 4. Past Work: Practical compilation of fexprs using partial evaluation 5. Current Work: Scheme & the more generic re-do 6. Future Work: Delimited Continuations, Layered Languages, DSLs --- class: center, middle, title # Fexprs Intro _Lisp Background_ --- (from Wikipedia) .fullWidthImg[] --- (from Wikipedia) .fullWidthImg[] --- # Background: Lisp A quick overview: <pre><code class="remark_code"> ; semicolon begins a comment 4 ; numbers and "hello" ; strings look normal and evaluate to themselves </code></pre> -- Essentially every non-atomic expression is a parentheses delimited list. This is true for: <pre><code class="remark_code">(+ 1 2) ; function calls, evaluates to 3 (if false (+ 1 2) (- 1 2)) ; other special forms like if (let ((a 1) (b 2)) ; or let (+ a b)) (lambda (a b) (+ a b)) ; or lambda to create closures (quote (1 a 3)) ; (equivalent to (list 1 'a 3) '(+ 1 2) ; expands to (quote (+ 1 2)) -> (list '+ 1 2) </code></pre> --- # Background: Lisp One of the key hallmarks of Lisp is macros <pre><code class="remark_code">(or a b) </code></pre> becomes <pre><code class="remark_code">(let ((temp a)) (if temp temp b)) </code></pre> --- # Background: Lisp This could be defined via <pre><code class="remark_code">(define-maco (or . body) (cond ((nil? body) #f) ((nil? (cdr body)) (car body)) (else (list 'let (list (list 'temp (car body))) (list 'if 'temp 'temp (car (cdr body))))))) </code></pre> But not hygenic! Could become so using explicit calls to _gensym_ --- # Background: Lisp Pattern matching, hygenic by default <pre><code class="remark_code">(letrec-syntax ((or (syntax-rules () ((or) #f) ((or a) a) ((or a b) (let ((temp a)) (if temp temp b))))))) </code></pre> --- # Background: Fexprs Something of a combo between the two - direct style, but naturally hygienic by default. <pre><code class="remark_code">(vau de (a b) (let ((temp (eval a de))) (if temp temp (eval b de)))) </code></pre> --- # Background: Fexprs - detail Ok, Fexprs are calls to combiners - combiners are either applicatives or operatives. Combiners are introduced with _vau_ and take an extra parameter (here called _dynamic_env_, earlier called _de_) which is the dynamic environment. <pre><code class="remark_code">(vau dynamicEnv (normalParam1 normalParam2) (body of combiner)) </code></pre> -- Lisps, as well as Kraken, have an _eval_ function. This function takes in code as a data structure, and in R5RS Scheme an "environment specifier", and in Kraken, a full environment (like what is passed as _dynamicEnv_). <pre><code class="remark_code">(eval some_code an_environment) --- # Background: Fexprs - detail - **Normal Lisp** (Scheme, Common Lisp, etc) -- - Functions - runtime, evaluate parameters once, return value -- - Macros - expansion time, do not evaluate parameters, return code to be inlined -- - Special Forms - look like function or macro calls, but do something special (if, lambda, etc) -- - **Kraken** (and Kernel) -- - Combiners -- - Applicatives (like normal functions, combiners that evaluate all their parameters once in their dynamic environment) -- - Operatives (combiners that do something unusual with their parameters, do not evaluate them right away) -- _Operatives can replace macros and special forms, so combiners replace all_ --- # Background: Fexprs - detail Combiners, like functions in Lisp, are first class. This means that unlike in Lisp, Kraken's version of macros and special forms are *both* first class. --- # Background: Fexprs - detail As we've mentioned, in Scheme _or_ is a macro expanding <pre><code class="remark_code">(or a b) </code></pre> to <pre><code class="remark_code">(let ((temp a)) (if temp temp b)) </code></pre> So passing it to a higher-order function doesn't work, you have to wrap it in a function: <pre><code class="remark_code">> (fold or #f (list #t #f)) Exception: invalid syntax and > (fold (lambda (a b) (or a b)) #f (list #t #f)) #t </code></pre> --- # Background: Fexprs - detail But in Kraken, _or_ is a combiner (an operative!), so it's first-class <pre><code class="remark_code">(vau de (a b) (let ((temp (eval a de))) (if temp temp (eval b de)))) </code></pre> So it's perfectly legal to pass to a higher-order combiner: <pre><code class="remark_code">> (foldl or false (array true false)) true </code></pre> --- # Background: Fexprs - detail <pre><code class="remark_code"> foldr: (let (helper (rec-lambda recurse (f z vs i) (if (= i (len (idx vs 0))) z (lapply f (snoc (recurse f z vs (+ i 1)) (map (lambda (x) (idx x i)) vs)))))) (lambda (f z & vs) (helper f z vs 0))) </code></pre> (lapply reduces the wrap-level of the function by 1, equivalent to quoting the inputs) --- # Background: Fexprs - detail <pre><code class="remark_code"> foldr: (rec-lambda recurse (f z l) (if (= nil l) z (lapply f (list (car l) (recurse f z (cdr l)))))) </code></pre> (lapply reduces the wrap-level of the function by 1, equivalent to quoting the inputs) --- # Background: Fexprs - detail <pre><code class="remark_code"> foldr: (rec-lambda recurse (f z l) (if (= nil l) z (f (car l) (recurse f z (cdr l))))) </code></pre> --- # Background: Fexprs - detail All special forms in Kaken are combiners too, and are thus also first class. In this case, we can not only pass the raw _if_ around, but we can make an _inverse_if_ which inverts its condition (kinda macro-like) and pass it around. <pre><code class="remark_code">> (let ((use_if (lambda (new_if) (new_if true 1 2))) (inverse_if (vau de (c t e) (if (not (eval c de)) (eval t de) (eval e de)))) ) (list (use_if if) (use_if inverse_if))) (1 2) </code></pre> What were special forms in Lisp are now just built-in combiners in Kraken. *if* is not any more special than *+*, and in both cases you can define your own versions that would be indistinguishable, and in both cases they are first-class. --- # Motivation and examples 1. Vau/Combiners unify and make first class functions, macros, and built-in forms in a single simple system 2. They are also much simpler conceptually than macro systems while being hygienic by default 3. Downside: naively executing a language using combiners instead of macros is exceedingly slow 4. The code of the operative combiner (analogus to a macro invocation) is re-executed at runtime, every time it is encountered 5. Additionally, because it is unclear what code will be evaluated as a parameter to a function call and what code must be passed unevaluated to the combiner, little optimization can be done. --- # Solution: Partial Eval 1. Partially evaluate a purely functional version of this language in a nearly-single pass over the entire program 2. Environment chains consisting of both "real" environments with every contained symbol mapped to a value and "fake" environments that only have placeholder values. 3. Since the language is purely functional, we know that if a symbol evaluates to a value anywhere, it will always evaluate to that value at runtime, and we can perform inlining and continue partial evaluation. 4. If the resulting partially-evaluated program only contains static references to a subset of built in combiners and functions (combiners that evaluate their parameters exactly once), the program can be compiled just like it was a normal Scheme program --- # Intuition Macros, especially *define-macro* macros, are essentially functions that run at expansion time and compute new code from old code. This is essentially partial evaluation / inlining, depending on how you look at it. It thus makes sense to ask if we can identify and partial evaluate / inline operative combiners to remove and optimize them like macros. Indeed, if we can determine what calls are to applicative combiners we can optimize their parameters, and if we can determine what calls are to macro-like operative combiners, we can try to do the equivalent of macro expansion. For Kraken, this is exactly what we do, using a specialized form of Partial Evaluation to do so. --- # Challenges So what's the hard part? Why hasn't this been done before? - Detour through Lisp history? Determining even what code will be evaluated is difficult. - Partial Evaluation - Can't use a binding time analysis pass with offline partial evaluation, which eliminates quite a bit of mainline partial evaluation research - Online partial evaluation research generally does not have to deal with the same level of partially/fully dynamic and sometimes explicit environments - woo --- # Research - *Practical compilation of Fexprs using partial evaluation* - Currently under review for ICFP '23 - Wrote partial evaluator with compiler - Heavily specialized to optimize away operative combiners like macros written in a specific way - Prototype faster than Python and other interpreted Lisps - Static calls fully optimized like a normal function call in other languages - Dynamic calls have a single branch of overhead - if normal applicative combiner function like call, post-branch optimized as usual - Optimizes away Y Combinator recursion to static recursive jumps (inc tail call opt) - Bit of an odd language: purely functional, array based, environment values --- # Base Language: Syntax $$ \newcommand{\alt} {\mid} \newcommand{\kraken} {\textit{Kraken}} \newcommand{\kprim} [2] {\langle #1~\textbf{#2} \rangle} \newcommand{\kenv} [3] {\langle \langle #1~|#2,~#3 \rangle \rangle} \newcommand{\kcomb} [5] {\langle \textbf{comb} ~ #1 ~ #2 ~ #3 ~ #4 ~ #5\rangle} \newcommand{\keval} [2] {[\text{eval} ~ #1 ~ #2]} \newcommand{\kcombine} [3] {[\text{combine} ~ #1 ~ #2 ~ #3 ]} $$ .mathSize8[ $$ \begin{array}{rcll} n & \in & \mathbb{N} & \text{(Integers)} \\\ s & \in & Symbols & \\\ o & \in & \kprim{1}{eval}, \kprim{0}{vau},\kprim{1}{wrap}, \kprim{1}{unwrap}, & \\\ &&\kprim{0}{if0}, \kprim{0}{vif0}, \kprim{1}{int-to-symbol},&\\\ &&\kprim{1}{symbol?}, \kprim{1}{int?}, \kprim{1}{combiner?},\kprim{1}{env?},&\\\ &&\kprim{1}{array?}, \kprim{1}{len}, \kprim{1}{idx}, \kprim{1}{concat},&\\\ &&\kprim{1}{+}, \kprim{1}{<=} &\text{(Primitives)}\\\ E &:=& \kenv{(s \leftarrow T)\dots}{}{E} \alt \kenv{(s \leftarrow T)\dots}{s' \leftarrow E}{E} & \text{(Environments)}\\\ A &:=& (T \dots)& \text{(Arrays)}\\\ C &:=& \kcomb{n}{s'}{E}{(s\dots)}{T} & \text{(Combiners)}\\\ S &:=& n \alt o \alt E \alt C & \text{(Self evaluating terms)}\\\ V &:=& S \alt s \alt A & \text{(Values)}\\\ T &:=& V \alt AT & \text{(Terms)}\\\ AT &:=& \keval{T}{E} \alt \kcombine{T}{(T\dots)}{E} & \text{(Active terms)}\\\ \end{array} $$ ] --- # Base Language: Contexts $$ \newcommand{\Ctxt} {\mathcal{E}} \newcommand{\InCtxt} [1] {\Ctxt[#1]} $$ .mathSize8[ $$ \begin{array}{rcl} \Ctxt &:=& \square \alt \kcombine{\Ctxt}{(T\dots)}{E} \alt \kcombine{T}{(\Ctxt,T\dots)}{E}\\\ && \alt \kcombine{T}{(T\dots,\Ctxt,T\dots)}{E} \alt \kcombine{T}{(T\dots,\Ctxt)}{E}\\\ \end{array} $$ ] --- # Base: Small-Step Semantics .mathSize8[ $$ \begin{array}{rcl} \InCtxt{E} &\rightarrow& \InCtxt{E'} ~ (\text{if } E \rightarrow E')\\\ \keval{S}{E} &\rightarrow& S\\\ \keval{s}{E} &\rightarrow& lookup(s,E)\\\ \keval{(T_1~T_2\dots)}{E} &\rightarrow& \kcombine{\keval{T_1}{E}}{(T_2\dots)}{E}\\\ \\\ \kcombine{\kcomb{(S~n)}{s'}{E'}{(s\dots)}{Tb}}{(V\dots)}{E} &\rightarrow& \kcombine{\kcomb{n}{s'}{E'}{s}{Tb}}{\\\&&\keval{V}{E}\dots}{E}\\\ \kcombine{\kcomb{0}{s'}{E'}{(s\dots)}{Tb}}{(V\dots)}{E} &\rightarrow& \keval{Tb}{\kenv{(s \leftarrow V)\dots}{s' \leftarrow E}{E'}}\\\ \\\ \kcombine{\kprim{(S~n)}{o}}{(V\dots)}{E} &\rightarrow& \kcombine{\kprim{n}{o}}{(\keval{V}{E}\dots)}{E}\\\ \end{array} $$ ] --- # Base: Selected Primitives .mathSize8[ $$ \begin{array}{rcl} \kcombine{\kprim{0}{eval}}{(V~E')}{E} &\rightarrow& \keval{V}{E'}\\\ \kcombine{\kprim{0}{vau}}{(s'~(s\dots)~V)}{E} &\rightarrow& \kcomb{0}{s'}{E}{(s\dots)}{V}\\\ \kcombine{\kprim{0}{wrap}}{\kcomb{0}{s'}{E'}{(s\dots)}{V}}{E} &\rightarrow& \kcomb{1}{s'}{E'}{(s\dots)}{V}\\\ \kcombine{\kprim{1}{unwrap}}{\kcomb{1}{s'}{E'}{(s\dots)}{V}}{E} &\rightarrow& \kcomb{0}{s'}{E'}{(s\dots)}{V}\\\ \kcombine{\kprim{0}{if0}}{(V_c~V_t~V_e)}{E} &\rightarrow& \kcombine{\kprim{0}{vif0}}{\\\&&(\keval{V_c}{E}~V_t~V_e)}{E}\\\ \kcombine{\kprim{0}{vif0}}{(0~V_t~V_e)}{E} &\rightarrow& \keval{V_t}{E}\\\ \kcombine{\kprim{0}{vif0}}{(n~V_t~V_e)}{E} &\rightarrow& \keval{V_e}{E} ~\text{(n != 0)}\\\ \kcombine{\kprim{0}{int-to-symbol}}{(n)}{E} &\rightarrow& 'sn ~\text{(symbol made out of the number n)}\\\ \kcombine{\kprim{0}{array}}{(V\dots)}{E} &\rightarrow& (V\dots)\\\ \end{array} $$ ] --- # Selected Explanations .mathSize9[ - \\(\kprim{0}{eval}\\): evaluates its argument in the given environment. - \\(\kprim{0}{vau}\\): creates a new combiner and is analogous to lambda in other languages, but with a "wrap level" of 0, meaning the created combiner does not evaluate its arguments. - \\(\kprim{0}{wrap}\\): increments the wrap level of its argument. Specifically, we are "wrapping" a "wrap level" n combiner (possibly "wrap level" 0, created by *vau* to create a "wrap level" n+1 combiner. A wrap level 1 combiner is analogous to regular functions in other languages. - \\(\kprim{0}{unwrap}\\): decrements the "wrap level" of the passed combiner, the inverse of *wrap*. - \\(\kprim{0}{if}\\): evaluates only its condition and converts to the \\(\kprim{0}{vif}\\) primitive for the next step. It cannot evaluate both branches due to the risk of non-termination. - \\(\kprim{0}{vif}\\): evaluates and returns one of the two branches based on if the condition is non-zero. - \\(\kprim{0}{int-to-symbol}\\): creates a symbol out of an integer. - \\(\kprim{0}{array}\\): returns an array made out of its parameter list. ] --- # Less Interesting Prims .mathSize9[ - \\(\kcombine{\kprim{0}{type-test?}}{(A)}{E}\\): *array?*, *comb?*, *int?*, and *symbol?*, each return 0 if the single argument is of that type, otherwise they return 1. - \\(\kcombine{\kprim{0}{len}}{(A)}{E}\\): returns the length of the single array argument. - \\(\kcombine{\kprim{0}{idx}}{(A~n)}{E}\\): returns the nth item array A. - \\(\kcombine{\kprim{0}{concat}}{(A~B)}{E}\\): combines both array arguments into a single concatenated array. - \\(\kcombine{\kprim{0}{+}}{(A~A)}{E}\\): adds its arguments - \\(\kcombine{\kprim{0}{<=}}{(A~A)}{E}\\): returns 0 if its arguments are in increasing order, and 1 otherwise. ] --- # Base Language Summary - This base calculus defined above is not only capable of normal lambda-calculus computations with primitives and derived user applicatives, but also supports a superset of macro-like behaviors via its support for operatives. - All of the advantages listed in the introduction apply to this calculus, as do the performance drawbacks, at least if implemented naively. Our partial evaluation and compilation framework will demonstrate how to compile this base language into reasonably performant binaries (WebAssembly bytecode, for our prototype). --- class: center, middle, title # Slow -- *so slow......* --- # Partial Eval: How it works - Online, no binding time analysis - Partially Evaluate combiners with partially-static environments - Prevent infinate recursion by blocking on - Recursive calls underneath a partially evaluated body - Recursive path to *if* - Track call frames that need to be real to progress on every AST node - Can zero-in on areas that will make progress - Also tracks nodes previously stopped by recursion-stopper in case no longer under the frame that stopped the recursion - Evaluate derived calls with parameter values, inline result even if not value if it doesn't depend on call frame --- # Partial Eval Semantics: .pull-left[] .pull-right[] --- # Partial Eval Semantics: .pull-left[] .pull-right[] --- # Partial Eval Semantics: .pull-left[] .pull-right[] --- class: center, middle, title # Optimizations --- # "The Trick" - Sorta... <pre><code class="remark_code">(lambda (f) (f (+ 1 2))) </code></pre> To something like <pre><code class="remark_code">function(f): if wrap_level(f) == 1: f(3) else: f([`+ 1 2]) </code></pre> - Insert runtime check for dynamic call sites - When compiling in the wraplevel=1 side of conditional, further partial evaluate the parameter value - Only a single branch of overhead for dynamic function calls --- # Lazy Environment Instantiation <pre><code class="remark_code">(lambda (f) (f)) </code></pre> <pre><code class="remark_code">function(f): if uses_env(f): env_cache = make_env() f(env_cache) else: f() </code></pre> Not only do we ask if *f* evaluate its parameters, but also does it take in an environment containing `{ f: <>, ...}`, etc --- # Type-Inference-Based Primitive Inlining For instance, consider the following code: <pre><code class="remark_code">(cond (and (array? a) (= 3 (len a))) (idx a 2) true nil) </code></pre> - Call to *idx* fully inlined without type or bounds checking - No type information is needed to inline type predicates, as they only need to look at the tag bits. - Equality checks can be inlined as a simple word/ptr compare if any of its parameters are of a type that can be word/ptr compared (ints, bools, and symbols). --- # Immediately-Called Closure Inlining Inlining calls to closure values that are allocated and then immediately used: This is inlined <pre><code class="remark_code">(let (a (+ 1 2)) (+ a 3)) </code></pre> to this <pre><code class="remark_code">((wrap (vau (a) (+ a 3))) (+ 1 2)) </code></pre> and then inlined (plus lazy environment allocation) --- # Y-Combinator Elimination - When compiling a combiner, pre-emptive memoization - Partial-evaluation to normalize - Eager lang - extra lambda - eta-conversion in the compiler --- # Current Status 1. No longer *super* slow 2. Fixed most BigO algo problems (any naive traversal is exponential) 3. Otherwise, the implementation is slow (pure function, Chicken Scheme not built for it, mostly un-profiled and optimized, etc) 4. Compiles wraplevel=0 combs to a assert(false), but simple to implement. 5. Working through bugs - right now figuring out why some things don't partially evaluate as far as they should --- # Benchmarks - Fib - Calculating the nth Fibonacci number - RB-Tree - Inserting n items into a red-black tree, then traversing the tree to sum its values - Deriv - Computing a symbolic derivative of a large expression - Cfold - Constant-folding a large expression - NQueens - Placing n number of queens on the board such that no two queens are diagonal, vertical, or horizontal from each other --- # Results: Number of eval calls with no partial evaluation for Fexprs .mathSize8[ $$ \begin{array}{||c | c c c c c ||} \hline &Evals & Eval w1 Calls & Eval w0 Calls & Comp Dyn & Comp Dyn\\\ & & & & w1 Calls & w0 Calls\\\ \hline\hline Cfold 5 & 10897376 & 2784275 & 879066 & 1 & 0 \\\ \hline Deriv 2 & 11708558 & 2990090 & 946500 & 1 & 0 \\\ \hline NQueens 7 & 13530241 & 3429161 & 1108393 & 1 & 0 \\\ \hline Fib 30 & 119107888 & 30450112 & 10770217 & 1 & 0 \\\ \hline RB-Tree 10 & 5032297 & 1291489 & 398104 & 1 & 0 \\\ \hline \end{array} $$ ] Number of eval calls in Partially Evaluated Fexprs .mathSize8[ $$ \begin{array}{||c | c c c c c ||} \hline &Evals & Eval w1 Calls & Eval w0 Calls & Comp Dyn & Comp Dyn\\\ & & & & w1 Calls & w0 Calls\\\ \hline\hline Cfold 5 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\ \hline Deriv 2 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 0 \\\ \hline NQueens 7 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\ \hline Fib 30 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\ \hline RB-Tree 10 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 10 & 0 \\\ \hline \end{array} $$ ] --- # Results: Number of calls to the runtime's eval function for RB-Tree. The table shows the non-partial evaluation numbers -> partial evaluation numbers. .mathSize8[ $$ \begin{array}{||c | c c c c c ||} \hline &Evals & Eval w1 Calls & Eval w0 Calls & Comp Dyn & Comp Dyn\\\ & & & & w1 Calls & w0 Calls\\\ \hline\hline RB-Tree 7 & 2952848 -> 0 & 757932 -> 0 & 233513 -> 0 & 1 -> 7 & 0 -> 0\\\ \hline RB-Tree 8 & 3532131 -> 0 & 906548 -> 0 & 279379 -> 0 & 1 -> 8 & 0 -> 0\\\ \hline RB-Tree 9 & 4278001 -> 0 & 1097965 -> 0 & 3383831 -> 0 & 1 -> 9 & 0 -> 0\\\ \hline \end{array} $$ ] --- # Results: .pull-left[] .pull-right[] --- # Results: .pull-left[] .pull-right[] --- # Results: .pull-left[] .pull-right[] --- # Results: .pull-right[] .pull-left[] --- # Current Research - More normal language: purely functional Scheme - Environments are just association lists - Fully manipulateable as normal list/pairs - Partial evaluation that supports naturally-written operative combiners, like the running *or* example --- # Future - Partial Evaluation / Kraken evolution: - More standard Scheme - Environments as association-lists - More flexibly-written macro-like fexprs - Performance: Better Reference Counting, Tail-Recursion Modulo Cons - Implement Delimited Continuations as Fexprs - Allow type systems to be built using Fexprs, like the type-systems-as-macros paper (https://www.ccs.neu.edu/home/stchang/pubs/ckg-popl2017.pdf). --- class: center, middle, title # Backup Slides --- # Introduction Here's some test code: .run_container[ <div class="editor" id="hello_editor">; Of course (println "Hello World") ; Just print 3 (println "Math workssss:" (+ 1 2 4)) </div> ] -- .rerun_container[ <pre><code class="remark_code" id="hello_editor_output">output here...</code></pre> <button class="run_button" onclick="executeKraken(hello_editor_jar[1].toString(), 'hello_editor_output')">Rerun</button> <br> ]